His home life, in particular, is rendered in vivid detail. Wole's father, S. A. "Essay" Soyinka, was the local school headmaster and a figure of authority – that esteem often extending to Wole and his siblings

– and his mother, nicknamed "Wild Christian," fostered an atmosphere of exotic disarray and spontaneity, often inviting an array of boarders or 'strays' to room with her children. Far from being inconsistent or permissive, however, both of Wole's parent's were disciplinarians, his father more methodically so than his mother. Accordingly, the Soyinka household was at once an intellectual and communal haven in Aké and a stimulating and engaging childhood environment.

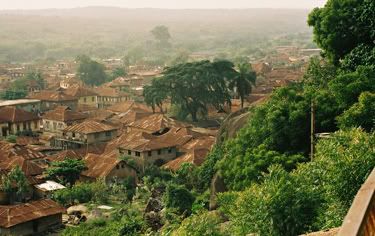

– and his mother, nicknamed "Wild Christian," fostered an atmosphere of exotic disarray and spontaneity, often inviting an array of boarders or 'strays' to room with her children. Far from being inconsistent or permissive, however, both of Wole's parent's were disciplinarians, his father more methodically so than his mother. Accordingly, the Soyinka household was at once an intellectual and communal haven in Aké and a stimulating and engaging childhood environment. Thus Aké: The Years of Childhood – as written from this naïve perspective – follows no strict chronology and is rich in sensory detail, imagery, and Yoruba words and variants. And as he grows throughout the book, spanning approximately the first eleven years of his life, Wole's perspective of himself and his reflection on his life in Nigeria and Nigeria's place in the world also mature.

Soyinka's memoir touches on both exciting and humorous themes, such as the episode in which 4-year-old Wole follows a marching band miles from home in a fit of boyish delight until he realizes he is helplessly lost, as well as more serious and painful experiences, such as his father's death and reflections on the commercialization and cultural degradation of his hometown street market. He also offers a child's view of brewing political change and social unrest, hinting at the impending fight for Nigerian independence as the book draws to a close.